Factsheet: Public-sector Employment and Wage Trends

Key Takeaways

- The share of public-sector employment in total employment has been relatively stable once reclassification effects are taken into account. In 2023 around 17% of the total workforce worked in the public sector. With NHS employment rising, the share of central government employment in public-sector employment is on the increase.

- Since mid-2021 average weekly earnings have been higher in the private than in the public sector. Since the beginning of the century this has only otherwise been the case in 2000. Moreover, there has been a compression of pay within the public sector. Historically average weekly earnings have been higher in the public than in the private sector as educational attainment and skills are generally higher in the former.

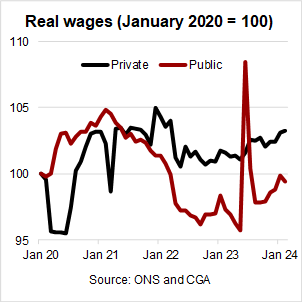

- Between mid-2021 and mid-2023 public-sector real wage growth was negative, with the result that real average weekly earnings have still not returned to pre-Covid levels. By contrast, real average weekly earnings in the private sector have been higher than pre-Covid with the exception of the furlough period in 2020.

The share of public-sector employment in total employment has been relatively stable once reclassification effects are taken into account

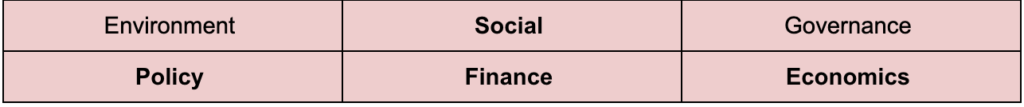

The share of public-sector employment in total UK employment dropped from 22% in 2010 to around 16.5% in 2018 and has since only gradually increased again. In absolute numbers public-sector employment was – at 5.9m – around 560,000 lower in 2023 than in 2010.

However, these headline changes reflect more sectoral reclassifications than actual trends. Among other reclassification changes, Further Education and Sixth Form College corporations in England were included in the public sector before mid-20212 but have been included in the private sector since then. Going the other way, Lloyds Banking Group plc and Royal Mail plc were reclassified from the public to the private sector at the end 2013. Once these reclassification changes are taken into account, the drop in the share of public-sector employment in total employment was much more modest and public-sector employment was in fact marginally higher in absolute terms in 2023 than in 2012.

The share of public-sector employment in total employment varies considerably across the regions of the UK. In 2023, in the East and South East only 15% of the total workforce was employed in the public sector. This contrasts with 26% in Northern Ireland.

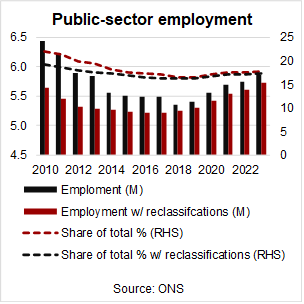

Within the public sector, central government is taking an ever larger employment share, rising from 44% in 2010 to 62% in 2023. Both local government and public corporations saw declines in their shares over that period.

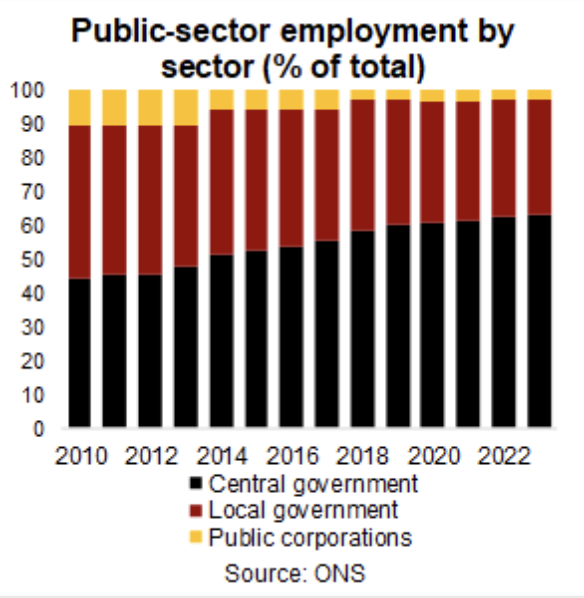

Much of this can be explained by the rapid rise in NHS employment, which went from 1.6m in 2010 to 2m in 2023. By contrast, employment in the civil service and in education remained reasonably stable over that period.

Since mid-2021 earnings have been higher in the private than in the public sector, reversing a long-term trend

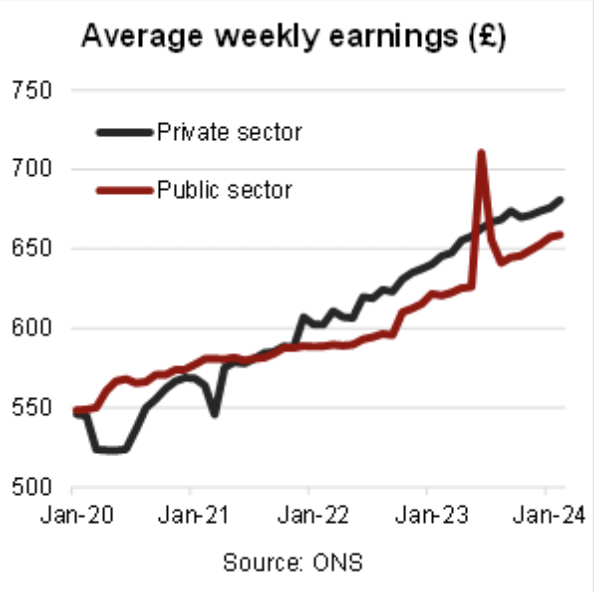

Average weekly earnings in the private sector dropped sharply at the onset of the Covid pandemic in early-2020 when many workers were moved to the government’s furlough employment support scheme. Average weekly earnings recovered quickly though and with the exception of March 2021 (when bonus pay was below trend) has seen steady growth since.

By contrast, average weekly earnings in the public sector continued to grow during the first year of the Covid pandemic but then trended sideways until early-2023. Since then it has grown more or less in line with private-sector earnings (the spike in June 2023 reflects the one-off bonus payment to NHS workers).

Notably, as a result of these diverging trends, average weekly earnings in the private sector have been higher than in the public sector since mid-2021.

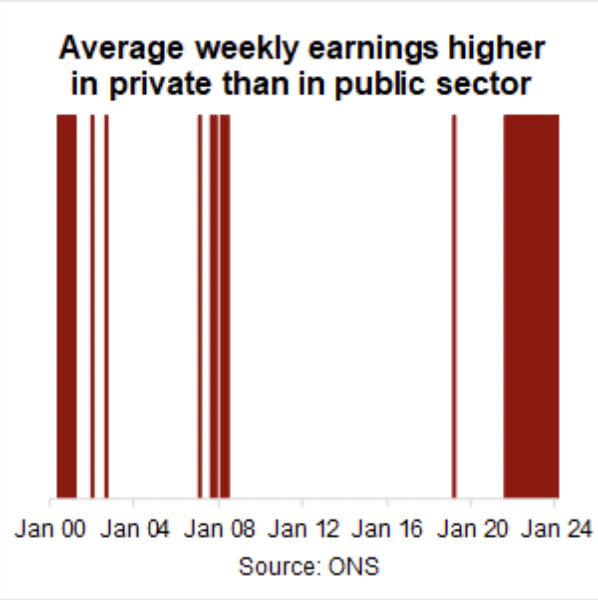

This contrasts with the long-term trend. In the 290 months between January 2000 and February 2024, average weekly earnings in the private sector were higher than in the public sector in only 49 of them (16%) – 30 of which since mid-2021. The last time average weekly earnings in the private sector were higher than in the public sector over several consecutive months was in 2000.

According to the Institute of Fiscal Studies, several professions in the public sector including nurses but in particular teachers and hospital doctors have experienced much worse pay growth than the average public-sector worker. This reflects a (deliberate) compression of public-sector pay within and across professions. This contrasts with developments in the private sector over the same period. Historically average pay in the public sector has been higher than in the private sector as the average level of educational attainment and skills is higher in the former than in the latter.

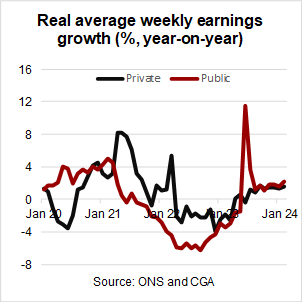

Between mid-2021 and mid-2023 public-sector real wage growth was negative

With consumer price inflation accelerating from early-2021 onwards (taking annual CPIH from 0.8% in December 2020 to a peak of 9.6% in October 2022), moderate nominal average weekly earnings growth initially turned into modest real growth and then negative real growth. This was particularly notable in the public sector: in the 24 months between July 2021 and June 2023, real average weekly earnings growth was negative in 22 of them. In the private sector this was the case in 14 out of those 24 months.

As a result (and ignoring the one-off spike in June 2023), real average weekly earnings in the public sector were well below their pre-Covid level between mid-2022 and late-2023 and are only now close to pre-pandemic levels. This contrasts with developments in the private sector, where real wages have been higher than pre-Covid since the end of the furlough period.

Why does it matter?

Public-sector pay accounts for a large part of the public-sector spending and as such plays an important role in the financial stability of local governments and other public-sector bodies. Recent earnings trends show a compression of public-sector pay within and across professions, with the result that public-sector average weekly earnings have fallen behind those in the private sector. This suggests that public-sector wages in general and for certain professions in particular face significant upward pressure, potentially straining public-sector budgets even further.

If you would like to discuss what insights and lessons you could take away from recent public-sector and private-sector employment and wage trends, please talk to us.

Suggested further reading

England Population

Local Government Capital Expenditure and Stock

Corporate Reporting Standards and Requirements

Climate Change

Factsheet: Local Government Capital Expenditure and Stock

Key Takeaways

- In 2022-23 English local authorities spent a third of their capital expenditure on housing and about a quarter on highways and transport. In 2022-23 capital expenditure, which was down by 7% in real terms on 2018-19, was mainly used for new constructions, conversion and renovations.

- The main source of revenue to finance capital expenditure were capital grants, followed by prudential borrowing. The sources of revenue have remained relatively stable between 2018-19 and 2022-23.

- The net capital stock of local government in the UK increased from 8% of GDP in 2000 to 14% of GDP in 2022. Other buildings and other structures make up the bulk of the net capital stock.

Capital expenditure by service

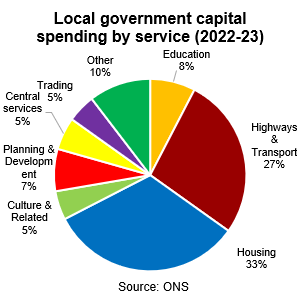

In Fiscal Year (FY) 2022-23 local authorities in England spent £27.5bn on capital expenditure. Of this spending, a third was on housing, just more than a quarter on roads and transport, and just less than a tenth on education. Planning and development services, central services, culture and related services and trading (i.e. the maintenance of civic halls, retail markets and industrial estates etc) together made up nearly a quarter, with the rest spread across services such as police, environment and fire and rescue.

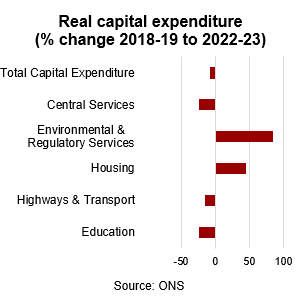

In real terms, the £27.5bn spent on capital expenditure in FY2022-23 represents a 7% decline from the 2018-19 level, with capital spending on education and central services falling by nearly a quarter. Local government capital spending on highways and transport dropped only slightly less (-15.3%). By contrast, local government capital spending on housing increased by nearly 50%, taking its share from 20% of the total in 2018-19 to a third in 2022-23.

Capital expenditure by category

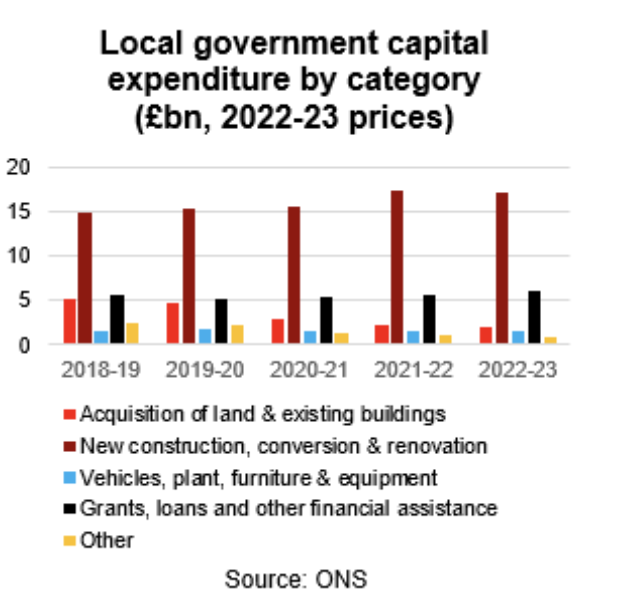

Of the £27.5bn spent in FY 2022-23, £17.2bn was spent on new construction, conversions and renovations, a further £1.9bn on the acquisition of land and existing buildings and £1.6bn on the purchase of vehicles, plant, furniture and other equipment. £6bn was given in the form of grants, loans and other financial assistance to other organisations to invest on behalf of the local authorities.

Over the period 2018-19 to 2022-23, the most notable development was the decline in investment in land and existing buildings. Amounting to £5bn in 2018-19, this more than halved over the following years, explaining the overall decline in local authority capital expenditure.

Revenue sources

The capital expenditure and revenue statistics do not fully match up, with the published expenditure data around £1.5bn lower than the revenue data.

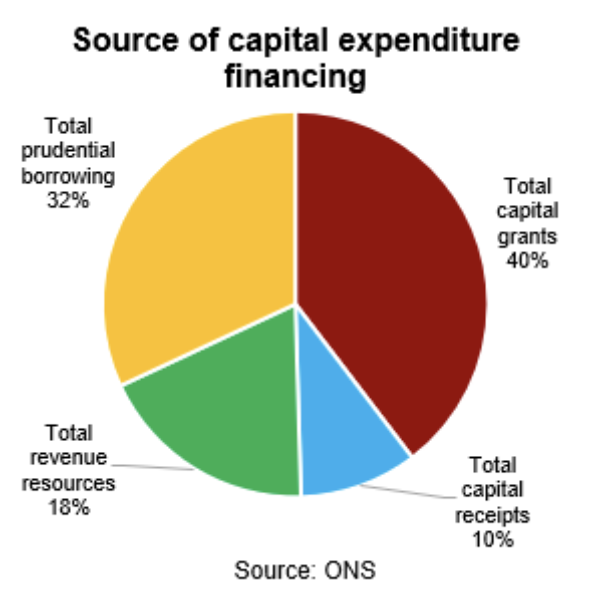

In FY 2022-23, 40% of the resources used to finance capital expenditure came from capital grants, around 20% from revenue resources (including from the housing revenue account, major repairs reserve and CERA) and 10% from capital receipts (incl

uding money received from the selling land, buildings or other capital assets). The remainder – just under a third – was in the form of prudential borrowing. These shares remained relatively stable between 2018-19 and 2022-23.

Local authority net capital stock

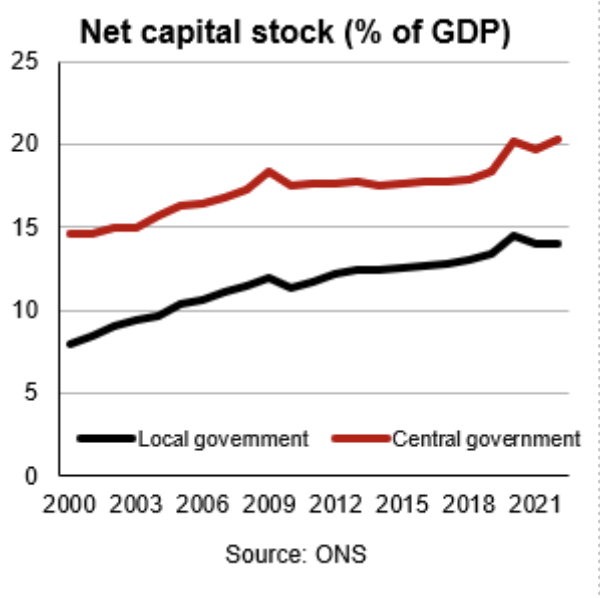

The Office for National Statistics publishes capital stock data for the UK only. As a share of GDP, the net capital stock of local government, that is the market value of fixed assets once deprecation is taken into account, increased from 8% in 2000 to 11% in 2010 and then 14% in 2022.

This is a much more notable increase than that for central government, which increased from 15% in 2000 to 20% in 2022. Other buildings and other structures have made up around 90% of the total net capital stock for local government throughout that period. The remainder is split between land improvements, ICT and other machinery and transport.

Why does it matter?

Local authorities play an important role in providing essential public services such as housing, transportation, and education. Capital expenditure and capital stock trends help to understand how this role is changing over time. Combined with local authority revenue trends they also illustrate the financing gap to be filled by prudential borrowing.

If you would like to discuss what insights and lessons you could take away from local authority capital expenditure and revenue trends in England, please talk to us.

Suggested further reading

UK Public Finances

England Population

Public-sector Employment and Wage Trends

Corporate Reporting Standards and Requirements

Climate Change

Factsheet: UK Public Finances

Key Takeaways

- In 2022-23 public-sector net borrowing excl. public-sector banks amounted to 5.1% of GDP. Central government is responsible for the overwhelming share of public-sector net borrowing.

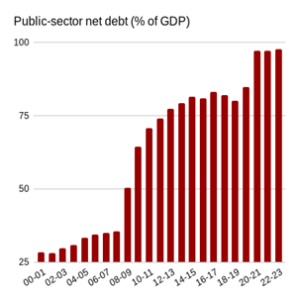

- In 2022-23 public-sector net debt was close to 100% of GDP – about average for an advanced economy. Public-sector debt jumped sharply during the financial crisis and increased further because of the Covid pandemic.

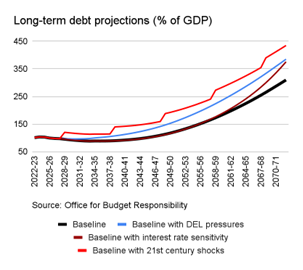

- Long-term projections show that net debt could increase to around 300% of GDP by the 2070s due to population ageing. It could be higher once other potential challenges are factored in.

Public-sector borrowing and debt

The UK public finances are generally reported on the level of the public sector excluding public-sector banks. This covers central and local government, public corporations, funded public-sector pensions and the Bank of England.

Public-sector net borrowing excluding public-sector banks (PSNB ex) amounted to £119.1bn in the first three quarters of the 2023-24 financial year (FY), the fourth highest on record for that period. In the second half of the last decade PSNB ex was generally around half as high in the respective periods.

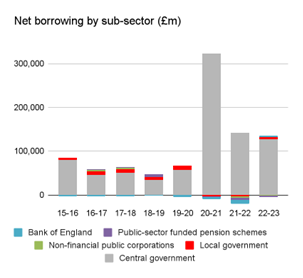

PSNB ex for the full FY 2022-23 amounted to £130.1bn, equivalent to 5.1% of GDP, marginally lower than in 2021-22 but significantly smaller than the 15% recorded in 2020-21 as a result of the Covid pandemic. The share is also lower than in any FY between 2008-09 and 2013-14.

Central government is historically responsible for most of the public-sector net borrowing. In 2022-23 central government and local government borrowed £127.8bn and £10.7bn respectively on a net basis, with non-financial public corporations and funded public-sector pensions reporting small surpluses. In previous years the Bank of England also recorded small surpluses. Transfers between the sub-sectors are netted out of the statistics.

The UK government’s preferred measure of debt is on a net basis excluding public-sector banks (PSND ex). In December 2023 PSND ex stood at 97.7% of GDP, a level last seen in the early 1960s. PSND ex increased from ~35% of GDP at the end of 2007-08 to ~85% of GDP mid last decade because of the financial crisis. It jumped to nearly 100% of GDP in 2020-21 as a result of the Covid pandemic.

International public finance comparisons are commonly made on a general government gross basis. As a share of GDP, UK gross general government debt was lower in 2022 (at 101.9%) than in France (at 111.1%), the United States (at 121.3%) but higher than in Germany (at 66.1%). The G7 average was 128%, much of it reflecting Japan’s high debt level (at 260.1% of GDP).

Fiscal plans and targets

The government announced in its 2023 Autumn Statement to reduce public-sector net borrowing from an estimated ~4.5% of GDP in 2023-24 to below 2% of GDP by 2027-28 so that net debt could start falling as a share of GDP within the next five years – one of the government’s fiscal targets. In 2023-24 social protection and health spending should make up nearly half of total managed expenditure, while debt interest payments account for around 10% – only marginally less than education spending.

Fiscal sustainability

The Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR), the UK’s official independent fiscal watchdog, regularly assesses the long-term sustainability of the UK public finances. The OBR projects the PSND ex to GDP ratio to fall slightly over coming years but then to increase sharply over coming decades as a result of population ageing. In the OBR’s baseline scenario PSND ex reaches 150% of GDP by mid-century and more than 300% by the early 2070s. According to the OBR, this is probably an underestimate as many potential risks are not considered in the baseline. For example, reasonably assuming that debt interest rates rise as the government becomes more indebted could take PSND ex to around 375% of GDP by the early 2070s.

Why does it matter?

The UK public finances are a crucial part of the economic and financial environment within which local authorities operate. Fiscal pressures are on the increase at all levels of government, while raising sufficient revenue remains challenging. Local authorities will need to learn to operate within tight fiscal constraints for years to come, making it ever more important to prioritise and seek efficiency gains.

If you would like to find out more about the topics discussed in this factsheet and what these might mean for your operations, please talk to us.

Suggested further reading